Building useful tools

I joined the Department for Education’s digital division in 2019 to work on Get School Experience. It’s a small service that lets people apply to spend a few days in a school, hopefully giving them a better idea of whether or not teaching is the career for them.

I remember how refreshing it felt to join an organisation where working collaboratively wasn’t just encouraged, it was the default. It’s even baked into the service standard:

If you develop your own patterns or components, share them publicly so others can use them.

My first job on the project was to work out how we were going capture all the information we needed from applicants. We knew we were going to be using the newly-released GOV.UK Design System, and because Rails was popular across government we thought there would be established tools we could lean on.

Forms are the main part of any transactional service, and Rails makes creating forms really straightforward. There must be something out there that combines the two.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t. We had a really tight deadline so we decided to repurpose the Ministry of Justice’s GOV.UK Elements form builder. It was an older library that was designed to work with GOV.UK Elements, the forerunner to the GOV.UK Design System. With a bit of work we had something useable but it wasn’t elegant and didn’t support some of the design system’s new accessibility features, like the error summary linking to the corresponding form input.

But, I’d found a gap. Something I thought should exist but didn’t. Something I was certain others would find useful. Something I thought I could do.

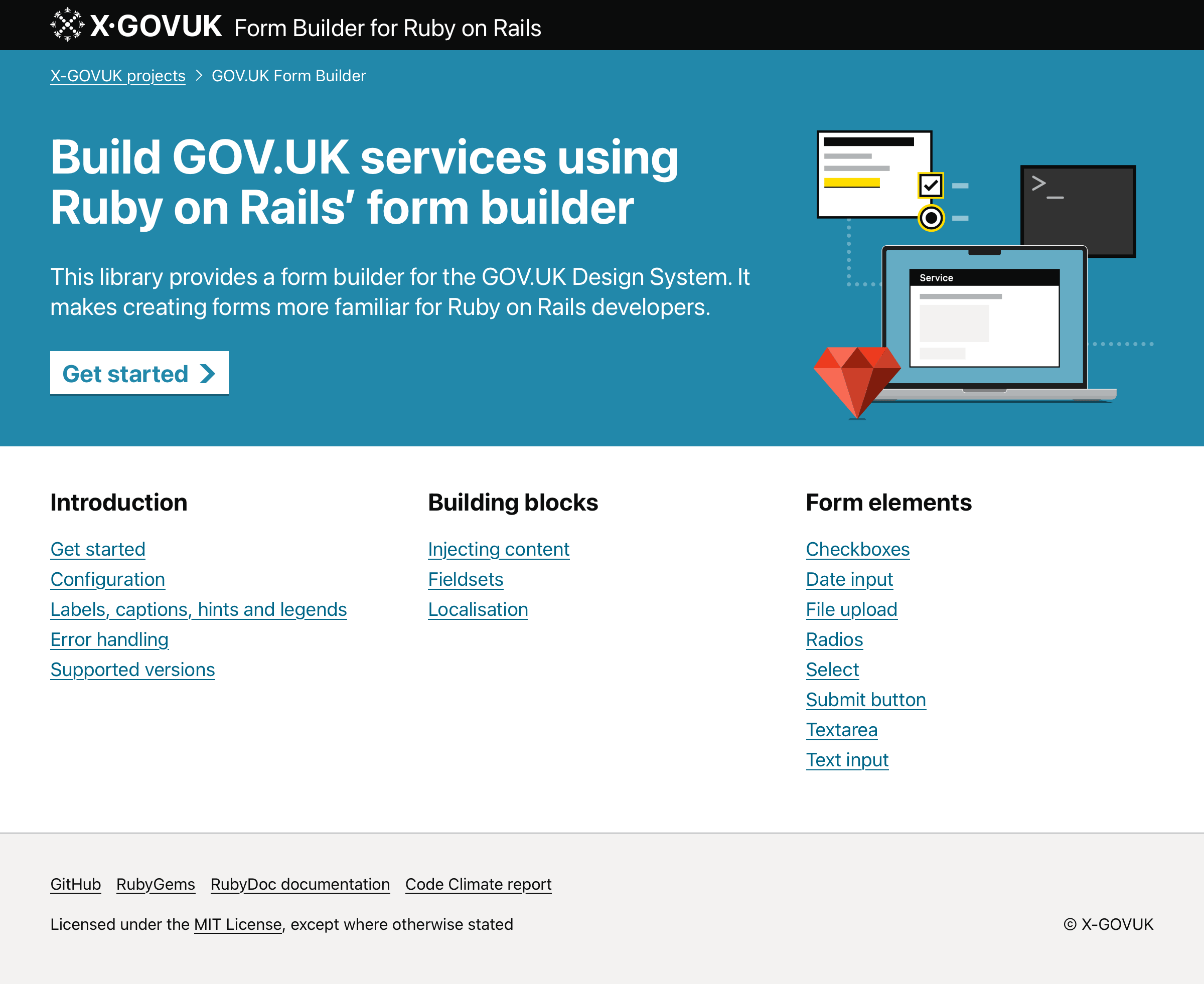

I decided to have a go at building and sharing a form builder from scratch and spent my free time over the next month working on it. I announced it via a very nervous-sounding YouTube screencast and, thankfully, it was well received.

It was my first time building and publishing a library, but having used plenty I had a good idea of what to prioritise if I wanted to make it a success. At the time, success meant a few other teams within the department might find it useful, I never imagined that there would be more than 130 live services using it.

So, in addition to having a good idea here’s my list of things that will help make your project successful.

1. Active development

Unmaintained repositories are likely to become a burden, and might even hold you back from upgrading your application. It’s a huge red flag. Even if new features aren’t constantly being added, keeping on top of dependencies and making sure the documentation is up to date will give visitors to your project some confidence it’s being looked after.

2. A responsive maintainer

Knowing there’s someone who will answer queries on Slack, respond to GitHub issues, fix bugs and keep the library up to date and in sync with the design system is a must. Without them, the only option is to fork the repository and maintain it yourself.

3. An intuitive design

The GOV.UK Design System has a reference implementation written in Nunjucks that provided inspiration but this had to feel like Rails. We use blocks instead of strings of HTML, we use snake_case instead of camelCase. If the ergonomics aren’t right, developers won’t use it.

4. Proper documentation

Good documentation is probably the best way to give projects an air of legitimacy. A user guide with copyable code snippets and fully rendered examples is a worthwhile investment, especially when it has fantastic artwork on the homepage (thanks Paul!)

5. Going the extra mile

While the upstream Nunjucks macros are a great starting point, I took every opportunity to make the developer experience a bit smoother.

Being able to make a tag blue with colour: blue instead of passing in classes: "govuk-tag--blue", or open a link in a new tab with new_tab: true rather than rel="noreferrer noopener" target="_blank" are small improvements, but they add up.

6. Encouraging contributions

This is a big one, but no library author is able to predict what teams will need. Ensuring the codebase is clean, tidy and well tested makes the process of contributing easier.

Contributions aren’t always fully-fledged pull requests, feature requests count too and they’ve helped make the libraries more useful for everyone.

So far, nearly all suggestions made have been accommodated.

7. Getting real users

I was incredibly lucky that the team building Apply for teacher training were just getting started when I launched the form builder. It’s one of the Department for Education’s flagship projects and if they are confident enough to use it hopefully others would be too.

Real users find real bugs and limitations, it’s crucial in taking your hobby project to the next level.

What’s left to build?

I’m most familiar with the Rails ecosystem for building GOV.UK services and many of the building blocks you’ll need already exist. You can:

- render content with govuk_markdown

- provide accessible autocompletion for fields with dfe-autocomplete

- easily write tests that make sure your service is working properly with govuk-rspec-helpers

- build pages with govuk-components

- generate forms with govuk-form-builder

- send emails and text messages via GOV.UK Notify with notifications-ruby-client

However, there are still some common features and patterns that haven’t been fully addressed and are often re-implemented.

Here are a few that spring to mind, you’ll probably find an example in every Rails service:

- a GOV.UK-themed admin tool like RailsAdmin or Administrate, to easily build admin interfaces for apps

- a multi page journey or wizard builder - there have been several attempts to solve this but there isn’t an established leader, at least until GOV.UK Wizardry is finished!

- a date validator that follows the the design system’s suggestion of individually validating the day, month and year

- a tool which collates validation errors your users trigger and displays them in a dashboard, to help you diagnose problems and create a better user experience

For an idea of which tools exist in your programming language or framework of choice, take a look at the X-GOVUK resources list.